Board bring-up is a phased process whereby an electronics system, inclusive of assembly, hardware, firmware, and software elements, is successively tested, validated and debugged, iteratively, in order to achieve readiness for manufacture. This process can take so long that, sometimes, a product never gets to market because it is succeeded by the next generation.

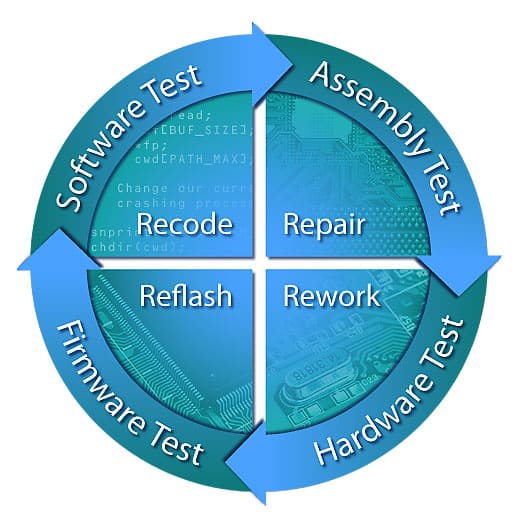

Any time a new prototype run is done as part of a new product introduction cycle, a repeatable set of steps are needed to ensure that the design is working as per specifications. Firstly, it must be verified that the board has been assembled correctly. Next, basic hardware test is needed (to ensure that the individual devices and buses/interconnects are operational – which involves testing power, clocks, and basic functional connectivity). After that, any firmware and low-level software must be debugged, to get the board operational; so that the next phase of testing may be applied, such as memory test or signal integrity validation. Finally, a system’s operating system is loaded, and any embedded software is checked. This sequence is represented visually here:

There are two very important things to note about this sequence:

- It is repeatable, within any given prototype run. Numerous boards are tested, debugged and validated in series and in parallel. At any given time, for example, some of the prototypes may be in hardware rework, whereas others may be stuck in reflash while engineers try to track down some obscure firmware bug.

- The repair/rework/reflash/recode cycle is repeated for each new prototype run. For complex systems, rarely does one go to volume manufacturing production immediately after the first prototype run. Issues are identified, and engineering change orders (ECOs) are often issued to correct defects which are only identified after the prototypes are subjected to rigorous testing.

Before I came to work for ASSET, I worked for a large telecommunications test equipment supplier, and we would always plan to have two prototype spins before going to volume production. This gave us time to get the bugs out of the system, get hardware in the hands of the firmware and software teams early, and meet any “we gotta get some designs to our top customers early!” demands from Sales and Marketing. And, given for example that there may have been 20 boards planned for the first prototype run, half of them didn’t work, so we had to make trade-offs: Marketing wouldn’t get a board for that important trade show, or the Technical Support engineers were just going to have to wait for the second prototype run before they could get their hands on one.

The problem was, the planned two prototype spins always ended up turning into three, four or even more. We always found problems with the second proto run that we didn’t catch with the first. And Marketing of course wanted some “feature creep” functionality added (it’s just one little change!) midway through development. So before we knew it, an extra year had gone by, our development plan was in shambles, and Intel, Xilinx, Broadcom, and other chip vendors had their next generation of silicon out. So I would be in these horrible meetings with Marketing where they would talk about canceling the project so we could start fresh with “a new design like what our competitors were working on”.

Has this ever happened to you? I can emphatically state that better validation, test and debug tools can make the difference between canceled products and successful ones.

One Response

Excellent…

We are doing this prototypes from last 3 years for a product. But, still its going on..